Remote learning cybersecurity and operations continuity advice from K-12 IT leaders who lived through it with you

For the past several weeks, we’ve been taking a look at the state of K-12 cyber safety and security in the year 2020. Previously, in The State of K-12 Cyber Safety & Security blog series, we did a 2019 K-12 cybersecurity recap through a remote learning lens. Then, we discussed the impact that EdTech migration is having on security and student data privacy. Finally, we took a deep-dive into student data privacy in remote learning. This post represents our final installment in this series, which culminated last week with a live panel discussion.

We were joined by Doug Levin, founder of The K-12 Cybersecurity Resource Center and creator of the K-12 Cyber Incident Map to discuss the trends he’s seeing now, compared with his research over the past several years and in the context of 2019 cyber safety and security. We were also joined by Neal Richardson, Director of Technology at Hillsboro-Deering School District in New Hampshire, and Greg Hogan, Network Data & Security Coordinator at Bibb County School District in Georgia.

K-12 IT teams were put through the proverbial meat grinder this year to get entire school operations shifted to remote learning, often with just a day or two notice. As a result, K-12 remote learning cybersecurity tended to take a backseat to the immediate needs of equipping students and faculty with devices, internet connection, and tools required to continue learning.

We wanted to sit down with Neal and Greg to hear their remote learning stories, learn what cybersecurity strategies worked for them, what challenges they faced, and what successes and/or lessons learned they’re pulling forward into the next school year. Here, we’re sharing some of the key takeaways from our conversation. You can also listen to the full, recorded panel discussion here.

![[FREE] K-12 IT Managers Discuss Cybersecurity & Student Data Privacy in Remote Learning. LEARN & SECURE >>](https://no-cache.hubspot.com/cta/default/6834707/eabbf966-79be-47cd-bb57-32b0554d9637.png)

Remote Learning Cybersecurity Successes

Both Neal and Greg agreed that there were two keys to their districts’ success when it came to remote learning cybersecurity. The first was that they already had strong cybersecurity tools and processes in place before everyone dispersed. They attributed the second key to success to their respective district’s cloud-first strategy.

“Thankfully, our district had a lot of good security practices in place, including at a cloud level. Securing our data at a cloud level puts us at an advantage because we’re not relying on the internal network to keep things secure when everybody scattered,” explains Greg. “As we let devices back onto the network next school year, we feel pretty confident that they should be relatively clean because we have cloud monitoring in place. We’re an Office 365 environment and a ManagedMethods customer and we’re using those two solutions to help maintain some control off-site. So, if those devices do have something wrong with them, it’s being reported in real-time we’re able to address it and lock down the account if necessary.”

Greg and the IT team at Bibb County have the district set up almost entirely in the cloud. This removes the need to allow students access to the internal network through VPNs, which can create cybersecurity issues. He also recommends using ClassLink, which they use to manage Single Sign-On for students, faculty, and staff accessing their various cloud-based edtech apps.

Neal also has his entire district in the cloud, mainly using G Suite for Education. “We’re 100% in the cloud, and I see no good reason to allow anyone back into my network.”

Neal is a big proponent of using a zero-trust security model and has structured his district’s cybersecurity infrastructure based on it. This security posture was a real advantage when his district’s schools closed with just one day notice. Being located in a geographically hilly area, there are many students and faculty who simply don’t get internet access to their homes—regardless of income level.

That meant that those students and teachers had to find places outside their homes to access remote classes and learning material. They had people parked in school parking lots, where they could access the building’s WiFi. They also had people using public networks in library, McDonald’s, and Dunkin’ Donuts parking lots. Does Neal have concerns about people using public networks?

“No. For the simple fact that I treat all my endpoints as hostile to begin with. Whether I own them or not I, there is zero trust there,” explains Neal.

Neal also attributes his district’s remote learning cybersecurity success to the recent state regulations requiring schools to be compliant with parts of the NIST cybersecurity framework. One benefit was that Neal dealt with far less 3rd party apps getting connected to his district’s domain and other EdTech security risks during the remote learning resources free-for-all.

“A part of the NIST requirements includes a data privacy agreement that we need to get signed before we can deploy any software. This means that the software vendor also needs to be compliant with that same subset of NIST 171 as we are, which limits what software is used on the devices,” Neal explained. “What it didn’t limit was every software vendor in the world throwing up their stuff saying, ‘everyone’s got free access until July. Come try it!’ That flooded us with questions from faculty and staff who thought that if it’s free, they can just use it…right? Well, no, we have a process and we need to get it vetted to ensure that it’s safe and secure and that it meets our standards before we can roll it out.”

![[FREE] K-12 IT Managers Discuss Cybersecurity & Student Data Privacy in Remote Learning. LEARN & SECURE >>](https://no-cache.hubspot.com/cta/default/6834707/eabbf966-79be-47cd-bb57-32b0554d9637.png)

Next School Year: Hybrid, Remote, or In-Class Learning?

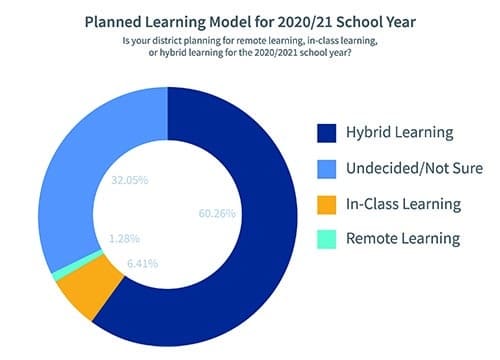

Live polling during the panel discussion found that 60.26% of K-12 IT leaders are planning for some sort of hybrid learning model for the next school year. 1.28% are planning for remote learning, 6.41% indicated in-class learning, and 32.05% said they were still undecided or not sure.

It’s particularly interesting to see the high rate of K-12 IT teams that are still undecided or unsure about their plan at the end of June. Hopefully, these teams are planning for multiple contingencies, versus not doing much in terms of planning yet. Districts will so themselves—and their students—a great disservice by not using this down-time to get processes and tools in place to make the next school year as productive as possible.

The debate around what would be acceptable for students in the next school year is hot, with pros and cons on both sides of the argument. Many people are still uncomfortable with returning to the classroom. And, with COVID-19 cases currently spiking again, it’s difficult to dismiss these concerns. There are also those that are big proponents of the hybrid learning model, arguing that it will better prepare students for life in college and/or the modern workforce.

But there are down-falls to remote and hybrid learning compared to in-class. The lack of personal and social development is a concern that should not be overlooked. Students will also have a more difficult time connecting with teachers and coaches in a meaningful way. These are people that have such strong, positive influences on social, emotional, and academic development in students. There are also concerns about how distracting hybrid learning might be for students and teachers alike, and how expensive it will be for cash-strapped schools that are already looking at probable further budget cuts.

The reality is that, even if schools are generally open to in-class learning, there will be some population of students (as well as, potentially, faculty and staff) who can’t re-enter the general population when classes resume. There are those people who are at high-risk for various health reasons. Many schools may also find themselves working with parents who just don’t feel comfortable sending their kids to school yet, regardless of what local officials are saying. Flexibility and creativity will be key in the coming year.

Remote Learning Silver Linings

During our panel discussion, we asked Neal and Greg about what they saw as silver linings in this otherwise lousy, chaotic scenario. Both agreed that one of the silver linings is simply the fact that we—as in the entire K-12 community—could do it. They also both expressed a sense of pride and gratitude for the IT teams they’re part of.

“We’re a small team, there’s two of us, and it demonstrated to our staff—the teaching staff, the administrators, the students—that this IT department can scale and meet their challenges. Whatever gets thrown at them, they don’t have to panic because IT is here to support you,” says Neal. “And I’m seeing that trend across K12 collectively. The entire IT space in K12 has risen to this challenge. It’s been incredible to see and hear the stories about the measures that we’re going through to ensure that students are getting educated.”

Neal also highlighted something that perhaps not many IT leaders are thinking about right now, which is the fact that every district should now have a functioning and tested Continuity of Operations Plan.

“Before, everyone was hesitant to document a plan if something like this were to happen. Well, guess what: it happened. Now, we just need to go back and write down what we did and we have a plan going forward if we need it again.”

Greg added that he saw the way that it forced them to try new things as a silver lining for Bibb County and for districts across the nation.

“Before we were kind of scared to try some things because we were afraid it would be too disruptive. Well, there’s nothing more disruptive than a pandemic,” says Greg. “So, now it allows us to kind of step outside the box and to think outside the box. We’re trying things that we wouldn’t normally try for fear of failure or being disruptive. In doing that, it allowed us to discover new ways of doing things and to get creative. And now we’re able to look at applying that creative mindset to next year. To me, that is a great silver lining and it’s a learning experience.”

K-12 IT teams were already largely overwhelmed, underdeveloped, and underfunded before COVID-19 threw districts into this extreme uncertainty. The coming school year will continue to challenge IT teams and K-12 districts as a whole. Cybersecurity, whether for remote, hybrid, and/or in-class learning is a necessity for all districts.

The 2020 CoSN K-12 IT Leadership Report found that cybersecurity is a top priority for K-12 IT leaders. Yet, 18% indicated that they have a full-time employee dedicated to cybersecurity, while 10% of survey respondents have an ad hoc approach to cybersecurity that does not have anyone assigned to this critical function. Further, 60% of districts allocate less than 10% of their technology budget to cybersecurity.

Remote learning cybersecurity isn’t going to make matters easier in the coming school year. IT teams will be challenged with a duality of issues impacting both their network and their cloud-based systems. Those that evolve their cybersecurity posture to meet the technology uses of their users will be in the best position to keep student and staff data secure. Those that do not will be more likely to end up on Doug’s K-12 Cyber Incident Map.